A few months ago—as with most of my books, hard to say exactly when and where—I chanced upon a a little volume of essays called Modern Poetics.1 It was published in 1965 as a $2.50 paperback, which I can only infer to mean that the contents have now been cast aside or otherwise long forgotten. It piqued my interest for one essay by W.H. Auden titled, in a not at all revelatory way, "The Poet & The City." The essay is mostly about writers and poets, but it is undergirded by a more sympathetic theme: work. It is prefaced by a quote from Henry David Thoreau,

There is little or nothing to be remembered written on the subject of getting an honest living. Neither the New Testament nor Poor Richard speaks to our condition. One would never think, from looking at literature, that this question had ever disturbed a solitary individual’s musings.2

A ‘softball’ quote to begin an essay on earning a living, I suppose, but neither I nor Thoreau ultimately found it to be true that nothing had been written on this matter. For all my love of Auden’s prose, he leaves out a key quote from Thoreau’s journal entry on that February day in 1851, “How to make the getting our living poetic! for if it is not poetic, it is not life but death that we get.” What is overlooked by Auden? The poet has never forgotten the laborer. Rather, poetry has not forget them, or more broadly, beauty has not abandoned those who are bent down by laborious tasks.

Our life in the Machine, among other things, is a thing we rightly feel must be conquered. Sometime during my elementary education I learned the motto of my home state, Labor Omnia Vincit, or “Labor Conquers All.” With the foolhardiness that is every young boy’s birthright, I accepted it and determined to “conquer all” by my labor. Quickly, maybe predictably, I was exhausted. As I grew older I applied so much attention to my studies, so much focus on the imperfections of my projects, so much scrupulosity to my spiritual life, labored with such intensity that more often than not I was sent back to my cave by worrisome thoughts of failure, only to emerge and repeat the cycle a few days later. I became, in the end, crippled by my labor. Auden soothingly draws from the Greeks,

No man can feel personal pride in being a laborer. A man can be proud of being a worker… but in our society, the process of fabrication has been so rationalized in the interests of speed, economy and quantity that the part played by the individual factory employee has become too small for it to be meaningful to him as work, and practically all workers have been reduced to laborers.

I made myself out to be merely a laborer, a body put to work, a “Cog in the Machine,” as they say. A worker, on the other hand, is one who applies themselves, either physically or mentally, to a task for the sake of creating or sustaining beauty. This is not to say that only the artist or poet is a ‘worker’ as such or that they are never laborers, but the privileged vocation of work is reserved for those who persevere in labor in order to sustain a life which partakes in beauty. A 2016 film, Paterson, shows how even ‘mundane’ jobs can be infused with meaning by a daily cultivation of beauty. The main character, Paterson, is a public transit bus driver who carries on extraordinarily mundane days, a kind of life you would probably expect as a public transit laborer. To give himself the sanity of a worker, Paterson writes poems about his town, his passengers, and his days as they pass by. By turning his labor into poetic form, his labor turns from meaningless tasks into work that begets beauty and infuses his life with meaning. Labor can, slowly and through great effort, became meaningful work when we apply it to older forms of beautiful life.

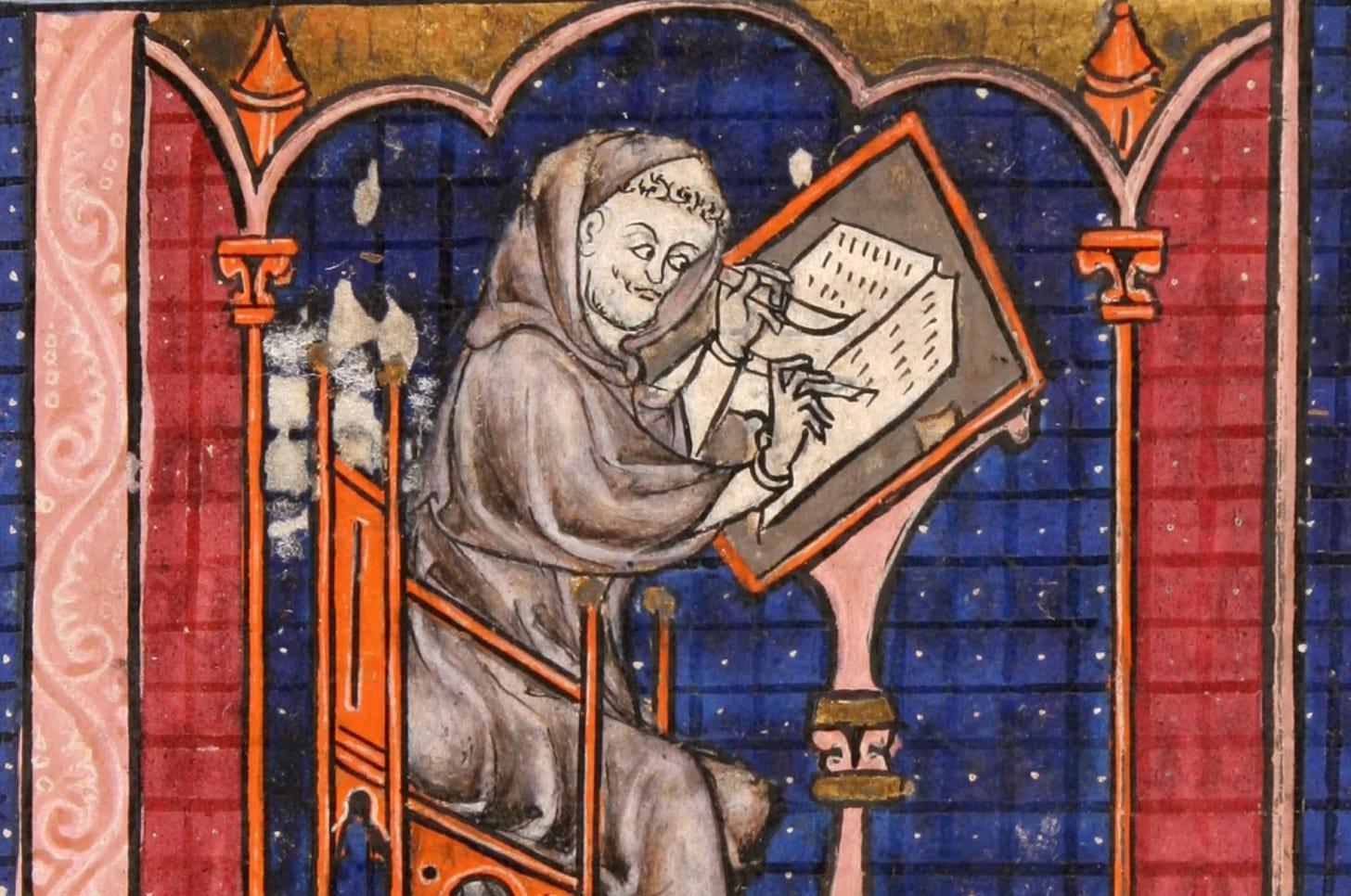

The tragedy of Digital Life is that technology has permeated our work so much that even occupations saved from the cold hands of industrialism—teaching, writing, crafting, studying (I could go on)— are being encroached upon by the efficiency of labor. What tasks which formerly offered a choice between labor and work now leave the worker with no option but to labor for production. Take illuminated manuscripts, for example. Why do we have these illustrious paintings in the margins of Bibles, prayer books, and literature in the early medieval era? Well likely, at first, because a monk who was given the task of copying af text got bored and doodled in the margins. With the dawn of digital creative tools and the demand for an efficient creative corpus, more and more writers, artists, and musicians are succumbing to what makes easy labor and losing the craft of what makes great work—they have no choice, in other words, but to leave the doodles for more “productive” work. Beautiful work is being swallowed because there is no room to discover its beauty in leisure. To liberally expound on Auden’s analysis of labor, we could say that work stands in direct opposition to the demands of “fabrication” or industrialism; work is embodied, slow, ornate, and quality. When we exchange the poetic form of work for the efficient form of labor, we inevitably kitschify what is produced. A hand carved chair will always be more beautiful than a industrially manufactured chair, and the former, more anachronistic craft will always grant the artist greater freedom and the beholder more appreciation.

How, then, do we avoid succumbing to the numbness, the death that labor subjects us to? We must, as Thoreau desperately exclaimed before, “make the getting of our living poetic!” Wendell Berry puts it another way in his essay “Poetry and Marriage: The Use of Older Forms,” we must hang on to the use of older forms.3 He writes, “When understood seriously enough, a form is a way of accepting and of living within the limits of creaturely life. We live only one life, and die only one death.” Ironically, the age of efficiency does not reward a conformity to forms as it is traditionally understood. Ironic, of course, because it is a form in and of itself, however diabolical it may be. This age it demands that the individual be “liberated” of any form and fashion for themselves their own identity apart from the one which may be prescribed by Tradition. What is promised by this age is a life made better by freedom, but what is delivered is a life bereft of beauty—beauty which is only possible within a given form. To discover beauty and even to generate it, we must adhere to a form.4 Berry relates poetry to forms evident in other aspects of life, especially marriage:

Forms join, and this is why forms tend to be analogues of each other and to resonate with each other. Forms join the diverse things that they contain; they join their contents to their context; they join us to themselves; they join us to each other; they join writers and readers; they join the generations together, the young and the old, the living and the dead. Thus for a couple, marriage is an entrance into a timeless community. So for a poet (or a reader), it is the mastery of poetic form. Joining the form, we join all that the form has joined.

If poetic forms are characterized by the wise use of language, to the distillation of language to its most succinct and beautiful essence, so the application of like forms to our lives may distill our life and time into its true, good, and beautiful essence. This is not to say that older forms are easier, if anything this essay has pointed to the fact that they are much more difficult and therefore, worthier. How do we find these forms to apply ourselves to? We could easily apply ourselves to the Machine form of efficiency and production though, chances are, if you’ve read this far that does not seem like the rosiest option. So where do we look? What will join us to diverse things, to one another? We must, as C.S. Lewis wrote, keep the “clean sea breeze” of Tradition blowing through our minds. Tradition, though we may be artificially severed from it, carries for us an abundance forms of leisure which we may find distill our lives down to its essence. By clinging to older forms we will find that our salvation from the Machine and the age of labor is in older forms of leisure—the book of poetry, the briar pipe, the hand tool, the lawn game, the crackling fire pit—and we are given the opportunity restore to ourselves that which the Machine steals away. We can, by older forms of leisure, slow down and behold the world before us. Much is at stake, for lest we conquer this age by Leisure, we destine ourselves to the pangs of labor.

I could say more, but this series is meant to fill in the gaps of the conversation occuring on Substack, not reiterate good work already done. So, I’d like to point you in the direction of three essays, one by myself, another penned by

and , and, finally an essay by Simone Weil.One of the first essays I published reflected on C.S. Lewis’s thoughts on Tradition from his preface of St. Athanasius’s On the Incarnation. “The Great Man” is not necessarily oriented toward leisurely activities (you could look to “On the Pleasure of Smoking” for that), though it does address the perennial need for old habits for a new age. I firmly hold that the best solutions for the present day have already been written, and to be a great thinker is only to mediate older ages to modern times.

The Great Man

"Our society at large has placed such a value on authenticity, uncommonness, and originality that we have forgotten the value of that which is quite mundane and typically shy away from anything that may pin us as not thinking for ourselves. We must, as Christian people, learn to deny the cultural urge to be original and outspoken. Not thinking for ourselves is precisely the virtue that we must strive for."

Since finding Substack, I’ve been surprised at the number of readers and writers interested in what is occuring in our time. It should be expected, I suppose, that great Upheaval would produce such thinkers, but I like to keep my expectations low.

and are a duo which have met my low expectations with hope. They continue to offer practical advice for “unmachining.” One of their most recent essays with the most delightful subtitle “How to be Weird in Public, and Private” is another exceedingly practical guide with great suggestions especially when it comes to leisure. I think they would agree, “older forms” are far superior in their ability to conquer our age.I have maintained, with both students and parents, that education is a training ground for leisure. The most ‘anachronistic’ and healthy forms of leisure are often derived from the experience of the school room—reading, writing, painting, crafting, and the like. By Divine Providence I found Simone Weil’s essay “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God” just a few months before I began my first year teaching last August. In her typically lucid and concise fashion, Weil shows how the classroom is a training ground for the soul—a proper education is oriented not toward the acquisition of information or success in a given subject or career, but to the cultivation of an attentive soul for our supreme and eternal end. I could not recommend this piece highly enough, though you may need to subject yourself to the slightly anachronistic and certainly older form of a library to find it.

Auden, W.H. “The Poet & the City” in Modern Poetics, ed. James Scully. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), 165-184.

Thoreau, Henry David. “January-April, 1851” in The Writings of Henry David Thoreau: Journal Vol. II, ed. Bradford Torrey. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1906), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59031/59031-h/59031-h.htm#Page_134

Berry, Wendell. “Poetry and Marriage: The Use of Old Forms” in What I Stand On: The Collected Essays of Wendell Berry 1969-2017, ed. Jack Shoemaker. (New York: The Library of America, 2019), 571-583.

For Christian readers, 1 Cor. 14:33 is often cited as a defense for liturgical worship. God, in order to be a Deity of peace and not confusion, prescribes order for our worship. It is within these forms that some of the most beautiful art and architecture has been produced, from Gregorian chant to Byzantine hymns to the art of DaVinci and the music of Bach. Arguably, this is the greater tragedy of innovation in liturgical forms—not only the beauty of the form itself but the occasion where truly beautiful work can occur.